Latest Posts

Dani McClain | Mama’s Writing

Mama’s Writing is Raising Mothers’ monthly interview series, created by Deesha Philyaw.

How has the experience of raising children shaped your own personal growth as a writer and as an individual?

Being pregnant and having a very young child motivated me. I worked on a piece about the Black maternal health crisis while in my third trimester, and it was published in The Nation when my daughter was about six months old. That article became the basis of the first chapter of my book WE LIVE FOR THE WE, which was published in 2019 when she was nearly 3. It’s a book about parenting and it’s a memoir, so everything I was experiencing in my daughter’s early months and years felt like potential material for the book.

As she has gotten older, I’ve taken on additional caregiving responsibilities in my family. I’ve also moved more behind the scenes in publishing. I worked as a ghostwriter on a memoir. I’ve served as a developmental editor on some fantastic nonfiction projects, supporting authors who are writing on topics ranging from education policy to private adoption to reactionary forces within Latino communities. I made the transition because in recent years my caregiving duties needed to be a priority. I needed to take on work that was more flexible and less deadline-driven. It’s been gratifying. I’ve realized that over the course of my 25-year-career I’ve become a solid editor and I enjoy coaching reporters and writers. I have this set of skills I’d been taking for granted and using solely to improve my own work. Now I’m in a more collaborative phase.

If you could go back and give yourself advice before becoming a parent, what would it be?

Expect the unexpected. Life is unfolding in ways I never could have imagined.

How do you navigate societal expectations or stereotypes as a Black parent in your writing while staying true to your authentic voice?

Social expectations don’t affect me much these days, maybe because if I’m writing under my own byline I’m typically reporting. The story is less about me and more about the sources I’m interviewing and the events I’m explaining.

What themes or topics do you find yourself drawn to explore in your work since becoming a parent, and why?

I’m increasingly interested in mental health and what works to keep children and teenagers engaged with the world and each other. My daughter is 7 and I am so thankful she has a deep joyfulness and optimism and curiosity about her. I don’t want to see that snuffed out as she gets older and understands more about the challenges we’re facing on this planet. I was recently awarded a Spencer fellowship for education reporting at Columbia’s journalism school, and I’ll be working on a project about how schools can successfully support students’ mental health. This is a story I would have pursued before becoming a parent, but now I’m even more driven to understand what makes children develop and maintain a sense of purpose and hope.

How do you handle creative challenges or setbacks?

I’m typically juggling several things professionally: editing books, maybe editing a story or two for a magazine project I started working with this year. I’m gathering string on the book I want to write next. The filmmaker Lydia Pilcher adapted a speculative fiction story I wrote in 2015 called “Homing Instinct” into a short film, and now we’re collaborating on a film installation based on the material. Sometimes projects pan out and sometimes they don’t. When they don’t, maybe I’m disappointed for a bit and then I move on to whatever else I need to tend to.

How do you navigate the fine line between sharing personal experiences in your writing while respecting the privacy of your family?

This hasn’t come up much since I wrote WE LIVE FOR THE WE. I remember running passages by people I’d written about so they wouldn’t be caught off guard after publication. I don’t write much about my daughter these days. That’s my way of respecting her privacy. I’m sure my thoughts on this will evolve as she grows and can decide for herself how she wants to shape her own identity and public presence. I’m a fairly private person. When in doubt, I pass on exposing much about myself or loved ones.

How do you carve out time for self-care, down time, and creative expression?

I just do it. My shoulders hurt? I get a massage if I can afford it. I want to take a walk and clear my head? I step outside. I want to lose myself in a novel? I ask my favorite local bookseller to recommend one. And when I need to focus on a deadline or piece of domestic labor or caregiving task, I do that. Then I try to savor the experience when I get to put my attention back on something relaxing or pleasurable.

How has your parenting journey impacted your perspective on your writing career and artistic aspirations?

I used to have more time to waste or to spend being a perfectionist. I also had more time to play and explore, to go down rabbit holes, to research things that may or may not turn into a story I could pitch and sell. Now I’m much more focused on locking in well-paying work, whether it showcases my own creativity or not. I turn elsewhere for some of the rush and validation I used to get through professional pursuits. I value the creativity I express through my relationships, through conversation. I value the meaning we make together on group chats. When I have an idea that feels important I leave myself a long voice note and hope I make use of it somehow, someday. Since becoming a parent, I get that time is finite. I understand effort and the necessity of fair compensation for all kinds of labor in a way I didn’t before.

How have other mother figures you have encountered in your community influenced your parenting? Your writing?

Oh, wow, read WE LIVE FOR THE WE for my chapters-long answer to this question. I am constantly observing and learning from others and accepting good guidance where it’s offered.

What advice would you give to other mothers who aspire to pursue their writing goals while raising a family?

Sometimes you might feel you’re falling behind and neglecting your creative goals. That’s likely because you are, and you shouldn’t berate yourself about it. You’re living your life and helping others live theirs. Caring for other human beings can be righteous, difficult work. We often think we should be able to do it while also engaging in rigorous intellectual work. Maybe some people can manage this, but it’s difficult for me. I am hopeful there will come a time when I can put more intellectual work on the front burner again. Until then, I intend to be present with these people with whom I’m lucky to be moving through life.

Who are your writer-mama heroes?

There are too many to name, and I know I’ll regret not naming someone. The writer Kathy Y. Wilson is on my mind, because her birthday is coming up, April 26th. She was a journalist, essayist, poet, playwright and art collector, among her many other talents. She died way too soon in 2022 at the age of 57. She didn’t birth children of her own but she was a mentor to me and a lot of other Cincinnati writers and artists of a certain generation. She was a kind of den mother to us, making sure we had places to read and publish our work and explore and laugh and love up on ourselves and each other. I miss her.

Dani McClain (she/her) reports on race, parenting and reproductive health and is a contributing writer at The Nation. She has written about play therapy and Black families’ experiences of the pandemic for The New York Times, the complicated legacy of Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger for Harper’s BAZAAR, and how to talk to kids about racism and policing for The Atlantic. Her work has been recognized by the National Lesbian & Gay Journalists Association, the National Association of Black Journalists and Planned Parenthood Federation of America. She received a James Aronson Award for Social Justice Journalism and served as a Type Media Center fellow. Earlier in her career, Dani reported on schools while on staff at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and worked as a strategist with organizations including Color of Change and Drug Policy Alliance. Her book We Live for the We: The Political Power of Black Motherhood was published in 2019 by Bold Type Books and was shortlisted in 2020 for a Hurston/Wright Legacy Award. She was the Cincinnati public library’s Writer-in-Residence in 2020 and 2021. Follow her on Instagram at @dani_mcclain and on Twitter at @drmcclain.

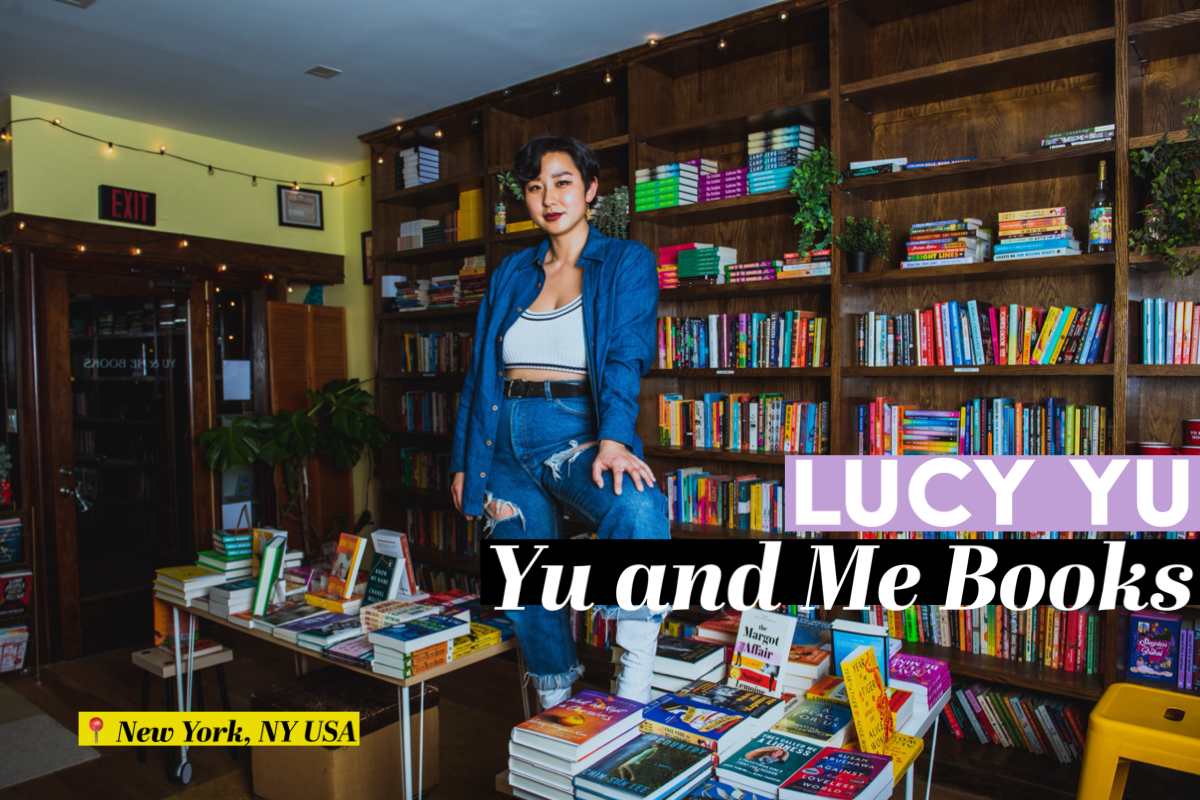

Shop Talk with Lucy Yu of Yu & Me Books

Lucy Yu is the founder and owner of Yu & Me Books, a “bookstore / café / bar” that focuses on the stories of immigrants and people of color. Yu & Me, which is based in Chinatown, Manhattan, NY, originally opened its doors in December 2021, and reopened in January 2024 after a fire. You can follow the bookstore on Instagram.

Tell me what led you to become a bookseller.

I believe books are the gateway to understanding experiences deeper outside of our own and they lead to true human connection. I’ve always gravitated towards literature because I’ve always been curious about people. During the pandemic, I feel that we all were restrained to just glimpses of connection which were fabricated by technology but left us aching for the real thing. I was hoping I wasn’t the only one that desired that, so I started to build out Yu & Me Books to create a community bookstore home to encompass all these intersectional ideals I wanted. It turns out I wasn’t the only one and now I’ve been a bookseller for over 2 years!

What role has literature (and seeing yourself represented in it, or not) played in your life?

Literature has been a pillar in my life and a structure I continue to hold onto when I’m feeling untethered. It’s grounding to read shared and new experiences in others because it fills me with the richness of existence. Without it, I would only live in the small bubble of my own world and I don’t want to be limited to that perspective. Reading a diverse spread of books has always challenged my brain to imagine more, rethink my own blind spots, and adjust to the ever changing world around me.

What do you see as the role of bookstores and booksellers in your community?

We are all part of an ecosystem together, giving and receiving new information to those we are surrounded by. Books are portals and we are constantly stretching what we know from engaging in new discussions of varying interests in our community. Bookstores, booksellers, and communities are intertwined in this push and pull of working together to understand the world around us and how we all fit in it.

What’s the most enjoyable and/or rewarding aspect of owning a bookstore for you?

The people, always. As we’re all managing the peak of existentialism through our shared grief from the pandemic and grappling with re-engaging with the world, the feeling of loneliness and isolation continues. But we are never alone in our grief or experiences. The more we are able to share that with each other, the more we are reminded of the joys of existence as well. By creating the bookstore, I feel like I’ve somehow created a touchpoint of hope for joy and connection. Through the stories we have on our shelves, we’ve created a safety in being able to share our stories with each other (usually over a drink). What more can you ask for in this life?

Yu & Me Books suffered extensive damage from a fire on July 4, 2023. Can you talk about the journey to rebuild and return to brick-and-mortar operation after last year’s setback?

I am absolutely still processing all of it. Immediately when the fire happened and after, my brain focused mostly on the logistics of taking care of my team, a rebuilding timeline, and trying to move as fast as possible back to our original home. I think it’s only now that I’ve really processed the grief that comes with losing the first version of my business and the person I was when I built it the first time.

After the fire, we had a temporary pop up location from September to the end of the year (in 2023) at the Market Line before reopening in our original location at the end of January this year. Opening the store the first time was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done in my life, and I never thought I would have to do it 3 times in total. I had to confront my worst fear of my business / baby being destroyed and it gave me the ultimate test of understanding how much this dream really meant to me. The fact that giving up was never an option gave me a clear answer of how seriously I took this dream. I wouldn’t be standing here without our incredible community, helping us every day and believing in us when we were too tired to believe in ourselves. It shattered my faux reality of needing to be hyper-independent to be successful in this life. The outpouring of love and support from close friends, family, and strangers gave me a reason to believe in the beauty of being able to rely on others and ask for help. Something I have to remind myself every day to believe in still.

It’s been a bittersweet journey, filled with maximum love, grief, joy, exhaustion, pain, and hope. Definitely a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Bookstores are more than just places for books; they provide gathering spaces for people. How has the local community received and supported your bookstore? Tell me about your favorite memory of Yu & Me books being a hub for the community.

We owe our continued existence to our community and the local community. Being a new business in Chinatown, it was of utmost importance for me to hear what Chinatown residents needed and try my best to provide what they were missing. Their needs constantly change, and so must we.

While we were shut down during the fire, I was so scared to ask for help but so many people didn’t even wait for us to ask. Some incredible fundraisers were thrown by others to raise money for Yu & Me Books and it still makes me emotional to think about it. Archestratus Books hosted a bake sale fundraiser for us; Astoria Bookshop raised money from their own book sales to support us; Books Are Magic fundraised for us as well, in addition to letting us use their space for events; and Book Club Bar let us host our book clubs there. Bánh by Lauren, which did a pop-up on almost all of our opening days and have become some of my closest friends, co-hosted a pop-up with us at Nudibranch in the East Village to raise money for the store the week after the fire. There were so many local fundraisers and others that emailed us from the Bay Area. The Rockwood Music Hall fundraiser was hosted by the band the Reflections, who have performed multiple times at our in-store open mic nights, hosted by author Ed Lin, and they put together an incredible lineup of artists to raise money for us.

The Hua Hsu paperback launch and fundraiser is one of the most memorable events for me. We hosted it the week before we opened our temporary pop up at the Market Line. 500 people showed up on the rooftop of New Design High School, a wonderful school in the Lower East Side that we’ve been partnering with for over a year. We had authors Ly Tran, Hannah Bae, Delia Cai, and Mary HK Choi read original work about Yu & Me Books and other bookstores they love, with Chanel Miller joining Hua as a conversation partner afterward. So many other small businesses and artists—including Win Son, Lam Thuy Vo, Naomi Otsu, Maaari, Good Fight, Randall Park, and Andrew Kuo—all donated their time and resources for a raffle and auction in conjunction with the event. Hua put together an incredible zine of authors and artists sharing their experiences of going to bookstores. He paid for all of it out of pocket and sold it at the event, with all proceeds going to Yu & Me. I couldn’t believe the amount of support we had just looking out at a massive crowd of people coming together for literature.

Tell me about a bookstore or literary community space that has inspired you—or, if you created your own because you saw a need, what did you imagine before founding Yu & Me?

I imagined a very small-scale experience of being able to put a smile on someone’s face when they walked in. I thought that if I could nail it in a recommendation to someone searching for something in their life, that would already be a successful day for me. But what that small act really encompasses is the need for others to understand us and the joy that comes when they do. And what Yu & Me Books has become is more beautiful than my wildest imagination.

Tell me about a program or service your bookstore offers, something you love that makes it Yu & Me.

This may be too simple, but friendliness is something that I value very highly on our team. We are kind to everyone who enters and it’s a simple act but I do feel like having that intertwined with a retail experience allows for more space for comfortability. We take that quality seriously in all the events that we host as well. We are also engaged in constant change and remaining malleable to the fluctuating needs of our surrounding community.

PC: Jacques Morel

You opened your bookstore during the coronavirus pandemic, in a time of increased anti-Asian racism and violence. How has that influenced the way you select books, curate author events, or advocate for Asian writers and readers?

I always wanted to represent a wide range of literature that included Asian-American authors and writers while showcasing the large variety of the diaspora. Unfortunately, anti-Asian racism and violence is not novel (i.e. Chinese Exclusion Act amongst many other examples) and so the books that I initially curated did not stem from the increase in awareness of these violent crimes that have been committed against us for generations. But these stories have always been important and are still important for everyone to know.

I think because I am Asian-American, the bookstore was falsely labeled as an Asian-American bookstore, but we are a bookstore for everyone that just happens to showcase more books focused on immigrants and writers of color. It’s a bookstore that has great books which I think everyone should read. My advocacy for Asian writers started when I realized it was difficult for me to find books written by people that looked like me or my family. But once I started researching, I realized there is a rich reserve of stories that have always been shared but not necessarily spotlighted. That’s the gap I saw, and I hoped my bookstore would be able to give others more access to the wonderful works I was reading.

What’s on the horizon for you and your team in the coming months or year? What are you looking forward to?

I’m looking forward to us restabilizing beyond survival. I feel like the most fortunate person to have the best team in the world and to be surrounded by incredible people that are so much better than me in so many aspects. We worked so hard last year to rebuild the store from the ground up. I’m looking forward to us finding more ways to enjoy life and to integrate more rest.

Black and Brown bookstore owners do the important work of curating, amplifying, and preserving the rich throughline of stories that feed us. They are vital members of our local and global communities. Where there is a movement, there are books. But who captures the stories of the booksellers themselves? In this column, SHOP TALK, profiling booksellers, Dara Mathis turns the lens onto Black and Brown bookstores around the world, honoring the journeys that bring them to our neighborhoods.

A Mirror of Memories

Julia Lee’s Biting the Hand: Growing Up Asian in a Black and White America is my story, too.

For the past several years, what has fueled me (or has been slowly burning me up, I can’t tell anymore) is the growing rage and fury that’s been inside me like a fireball. I often have visualized myself as Ryu from the 1980s video game, Street Fighter, who is ready to unleash his fireball attack. My problem is that I don’t know where, at what, or at whom I should unleash it. When I picked up Julia Lee’s memoir, Biting the Hand: Growing Up Asian in Black and White America, I immediately recognized that rage she kicks off with. For me, it’s rage about the patriarchy, anti-Asian hate, racism (both internalized and external), genocide, past self-hatred, and microaggressions that happen multiple times every day, the “model minority” myth, Japanese incarceration in World War II, the inordinate number of incarcerated Black and Brown men and women in the U.S., the school to prison pipeline – the list goes on and on.

But all this rage was the perfect foundation for diving into this book, where I felt a sense of validation and of being fully seen.

I found and saw myself in Lee’s stories and in her memories, especially when she describes the Korean concept of han and hwa-byung, both which do not have an equivalent English transition. Lee writes, “To use the language of modern psychology, hwa-byung is considered a “culture-bound syndrome” or “cultural concept of distress.” Typically seen in middle-aged Korean women of low socioeconomic status, its symptoms include rage, insomnia, depression, heart palpitations, heavy sighing, a rising heat in the body, and stomach problems. Some researchers attribute it to the accumulated resentment and sense of injustice suffered by Korean women trapped in a patriarchal social system. If han is the curse of being Korean, hwa-byung is the curse of being Korean and a woman.” I felt most seen right in those words and my heart leapt at my fate of this double curse.

Most of the time, I found myself reading this book with a fist in air and furiously highlighting passages while crying bittersweet tears of healing.

As a once-avid reader, finding books where I can see the inner parts of myself have been few and far between. I long avoided reading this memoir because I wasn’t sure I could handle it. I sobbed through Michelle Zauner’s Crying in H-Mart, which took me over a year to complete. Maybe it was just the right time, but I ended up voraciously devouring Biting the Hand in a matter of days. Most of the time, I found myself reading this book with a fist in air and furiously highlighting passages while crying bittersweet tears of healing. Lee asks herself the same questions I had been asking myself since kindergarten, when I realized that my ethnicity and racial identity was different from the majority in my school, “How could I reconcile my two warring selves without being torn apart? I love my mother but I hate my mother. I love being Korean but I hate being Korean. I love America but I hate America.”

With that constant inner battle, I experienced what I thought was a desire to be white, but Lee so aptly reminded me that I just really wanted to be seen and treated as a human being. I still feel this to this day. The category of “racial other” pulsated through me as I recalled my own childhood where adults and children alike asked me, “What are you?” with exasperation after asking if I was Chinese or Japanese. And even in today’s world, where people have now even begun to ask me things like, “Oh, are you Korean? Do you listen to K-Pop? Have you seen the latest K-drama on Netflix?”

K-pop is now a global phenomenon. In fact, according to Middlebury Language Schools, “College enrollment in Korean courses in the US increased by 95% between 2006 and 2016.” Korean food is popular, not looked down upon as it was when I was growing up. Kimchi is everywhere and even Trader Joe’s sells things like gochujang (red pepper paste), kim-bap, and bulgogi bowls. Even so, I still find myself asking the same question that Lee asks in the beginning of her book, “Who was I? Or rather, what was I? What did white people see when they looked at me?” I don’t want to be the sole representation of a country that I wasn’t born in, even though that’s where my roots are. I don’t want to be a token or to be that “Korean friend” – is it too much to ask to just be me and to be seen as just me?

I am still left with this question of what it even means to be seen as an individual since I’ve had to undo my own internalized white gaze. What does it even look like to be a human being who happens to be caught in all these intersectional identities? And where is my place in the racialized conversations of the pandemic and now? Do I even belong here? Lee points out, “Whiteness cast Asians as perpetual foreigners and the model minority, cast Black people as perpetual criminals and the problem minority, then sat on the sidelines to watch what happened.” This is where I have found myself for many long years, but Lee’s book has given me permission to leave that place and to shed the shame that has shrouded me for nearly half a century. It has led me to a place where I felt that all things had to be hashed out in this false narrative of the binary – that the cost of my liberation had to come at the cost of other racialized groups, especially my Black allies and friends. What I have come to realize, and what Lee plainly states in her book, is that there is an abundance for all of us. Standing by my Black allies and friends in solidarity is a part of my own liberation. I have been living in a mindset of scarcity, trying to hold on to my tiny crumb, without realizing that there is more than enough!

However, to do that, I need to know that I can be a force for my liberation – that I do have power and privilege that I can leverage. It was at this realization while reading Lee’s book that I understood what she meant by “biting the hand.” Being me and being human means that I have the ability and necessity to break away from the white gaze. I also need to see that I am different from the generation before me, and my child is going to be different from me. I am an evolving, living being with a choice. Actually, we are evolving, living beings with a choice. Will we choose to dismantle oppressive power structures, or will we perpetuate and uphold them? Will we allow for ourselves and for the next generation to evolve and flourish or will we drown one another in scarcity, exceptionalism, and individualism? Will we be courageous enough – be bold enough – and love ourselves enough to bite the hand that feeds us? I am grateful toJulia Lee for forging a path with her story, and I hope that it will inspire you to step forward and give yourself permission to reclaim your belonging, too.

Biting the Hand: Growing Up Asian in a Black and White America by Julia Lee. This book was originally published on April 18, 2023 by Henry Holt and Company

Ten Questions for Chin-Sun Lee

What inspired you to tell this story?

About eight years ago, I spent two consecutive summers in a hamlet in the Catskills, where I was able to observe small town life. As someone who’d lived mostly in large urban cities, I found the ecosystem of a rural community pretty fascinating. On one hand, it was predominantly white, so it was a new experience for me to feel how I stood out. On the other hand, I was surprised by how tolerant most people were toward each other, despite varying backgrounds of class, race, occupation, and sexual orientation. I think this had a lot to do with the fact that within a small confine, you had to accommodate, or the society around you would become dysfunctional. This was also just before the Trump era, and the divisiveness it ushered in, so I’m not sure if that tolerance remained or changed in that community since. In any case, I’ve always had a sociological bent, so this dynamic of compression was intriguing to me, and in my novel, I used it to create tensions that weren’t present in my lived reality. I also wanted to write a story told from the perspective of women who were vastly different from each other, to illustrate the subtle connections that can occur between women regardless of those differences—whether through friendship, enmity, or compassion despite enmity.

What did you edit out of this book?

This book went through several iterations, so it’s hard for me to recall exactly. But one significant edit happened early on, when I’d written an 8K-word chapter based on some tertiary characters, landlords of one of the main protagonists. After I wrote it, I realized that, while their story was fine, it didn’t propel the main narrative. It was a tangent. Still, while I might have wasted time and words going down that rabbit hole, it was an important lesson in realizing that, at a certain point in a novel, it does help to have a loose outline, even just breadcrumbs, so you don’t completely spin out of control. It’s especially challenging when you’re dealing with multiple characters. You have to convey the full complexity of your invented world, but stay focused on the predominant themes.

How did you know you were done? What did you discover about yourself upon completion?

Endings are so hit or miss for me. Sometimes they’re effortless, which is an amazing thing; sometimes I really struggle. I had a loose idea of the ending for this novel, but no concrete way to get there. And then, as I was writing toward what I knew would be the final chapter, an image and snippet of dialogue came to me, and it just felt absolutely right. When that happened, I was so relieved and grateful, because it really did seem like a gift from the universe. Having now written quite a few stories, a first novel, and wrapping up my second, I’ve learned to just have faith in myself, to believe that if I keep at it and stay in the world of my story, sooner or later its conclusion will reveal itself.

What was your agenting process like?

I started querying in late 2018, and while I had several full requests, it took eight months to find my agent. A few months in, I paused in my querying to revise the novel based on some initial feedback. My agent from the beginning was responsive, professional, and enthusiastic about my novel, but her agency moved offices at one point, which delayed and disrupted her reading, and everyone should know that reading queries for agents is extracurricular work; their existing clients are priority. By the time she expressed interest in having a conversation, I had drastically changed one character’s arc. She was on board with that, but had concerns about other aspects of the novel being too dark. But we had a great conversation and really vibed, so when I suggested sending her a revision in a few weeks, she agreed. After she read the revision, she offered representation. Then I did due diligence by allowing two weeks for other agents who had the manuscript to weigh in, and of course, once you have one offer, everyone else perks up. In the end, though, my gut told me to go with her, and I’ve never regretted that decision.

What was the best money you ever spent as a writer?

Not sure about the best, lol, but definitely the most money I ever spent as a writer was on tuition for my MFA at The New School—and while I really urge writers to carefully weigh whether that degree warrants the cost, for me it was worthwhile. I was working throughout grad school, and I got a partial scholarship, so it was a manageable expense. I also really needed the validation. Most importantly, I made so many wonderful friends who are still my beta readers and support system to this day.

How many hours a day do you write? Break down your typical writing day.

Ideally, I take care of emails and other miscellaneous tasks in the morning, then go to a local coffee shop to write for four or five hours. I’m a slow and careful writer, so for me, hitting 500 words is a good day’s work. Sometimes, that’s it for that day; other times, after dinner, I’ll keep on writing until late in the evening. Then there are the days I’m not able to touch the writing at all, due to other work or obligations. I will say for the past several months, toggling pre-publication tasks while trying to finish my second novel, I’ve been going at a relentless pace, working from morning till night, with very little reprieve. I’m pretty exhausted, but also so aware that a debut only happens once, so I want to put my whole heart and soul and energy into this process.

What are your top three tips to help develop your writing muscle?

Write into your obsessions—whatever feels hot or urgent. Try to stay in the world of your story, regardless of what life throws at you; even tinkering with a line or two or thinking about a plot point while brushing your teeth helps to not completely lose the thread. Choose specificity over abstraction.

What does literary success look like to you?

Having an actual readership, an audience; being able to survive financially, so that I can keep writing; continuing to publish and being an active part of the literary community.

What other authors are you friends with, and how do they help you become a better writer?

Oh gosh, there are so many! My most valued readers since grad school have been Adam Klein (editor of The Gifts of the State, author of The Medicine Burns and Tiny Ladies), along with Elizabeth Bull, Ryan D. Matthews, and Kate Angus (So Late to the Party). There’s also Laurie Stone (Streaming Now and Everything is Personal), L.J. Sysko (The Daughter of Man), Julie Bloemeke (Slide to Unlock), Brian O’Hare (Surrender), and Eric Sasson (Admissions), to name a few. All of them in their different ways have helped me either through careful critiques, supportive commiseration, loving encouragement, or stimulating conversations—usually a combination of all. I am extremely fortunate to know these people.

Who are you writing for?

I write for myself first, then for other women—or anyone interested in the lives of women.