As new parents, Dia and Neel had often heard from older couples in their families that the early years of marriage are rosy rosy rosy. True colors of a couple come out once they have a child. That’s when you have to adjust adjust adjust. This last line, aunties recycled more often, eyeing Dia.

Adjust, she told herself while locking the seatbelts around their one-year-old daughter, Taarini, in her child seat. Neel’s dad’s cousin brother was hosting the Diwali party for all of her extended families-in-law, the Samskaras, at his house in Mission Viejo. Dia and Neel hadn’t recovered from their fight over their vacation plans for Hawai’i but it was their first Diwali outing with Taarini so they decided to play social that evening. While driving, Neel turned on the sports channel. He knew how much Dia disliked the male anchor’s whiny voice alternating between a commentary on sports and politics with predictable quips on women celebrities. While driving in their pre-baby days, they’d mostly talk about their day at work, their latest with friends, travel destinations topping their list, post-retirement dreams, or listen to music they both enjoyed—The Beatles, Queen, U2, Bob Marley, A.R. Rahman—Neel cracking her up with his loud singing, mostly out of tune. Now, she couldn’t recall the last time they’d checked in with each other, held hands while driving as they used to, or looked into each other’s eyes before that habitual goodnight peck—blame it on the baby, the sleep deprivation, and the fatigue; blame it on five years of marriage and the monotony of seeing each other day after day after day, “midlife crisis” as goras would call it; blame it on the anger and frustration seething within from bumping into the same issues over and again, he accusing her of being antisocial and indifferent to his family, she accusing him of intimacy issues in marriage and an overattachment to his family.

Adjust, Dia told herself as she clasped an oxidized choker around her nape. She resisted the urge to turn down the radio volume, and the strong air conditioning in the car, another one of their frequent points of contention. Dia was always cold; Neel was always hot. Adjust. Dia wrapped a cashmere stole around her silk kurti and glared at her husband. The way he seemed focused on the road, she knew he wasn’t ready to call it a truce over Hawai’i. She wouldn’t either. Let him get it once and for all that his wife wasn’t a pushover, the dutiful daughter-in-law, eager to oblige. She deserved downtime, and she wouldn’t apologize for not wanting company during their trip, especially as a new family of three. She switched on her phone and logged into Instagram.

The party in Mission Viejo was the usual intergenerational affair, the older men discussing Trump’s America or Modi’s India in one side of the living room, the older women discussing the Mahabharata in the new TV production on the other side, the younger men discussing the Lakers by the bar, the younger women cooking in the kitchen, and a few others chaperoning their kids playing hide and seek or board games in the upper floor’s living room. As Neel took Taarini out of her car seat, his family took her and started passing her around, everyone doting upon the latest family addition. Since Taarini was born, Dia had grown invisible to her family-in-law, a feeling she’d grown to welcome, especially in these large parties where she’d trouble remembering everyone’s names and the ways in which they were related. She looked around for Neel’s younger cousins they were both close to, Kiran, Sherry, and Dia’s former roommate from her San Diego days, Maya, the one to introduce the new parents at a Halloween party in greater L.A.

After greeting different members of Neel’s family, Dia sat by the base of the staircase in the living room, sipping a Kingfisher. Neel joined her with an old-fashioned, bored quite likely with the sheer number of unknown faces at the party and the absence of his younger cousins who were stuck in traffic. As they watched the Lakers game on the TV, one of Neel’s older cousins sauntered toward them, a mango margarita in hand. Dia joined the small talk between the two—how California was facing yet another drought, how they never saw the new parents at Samskara parties anymore, how the turkey kababs wouldn’t last, they should run for their share, how the cousin should’ve made more samosas, three more families decided to join them last minute.

Neel praised the crispy dough of the spinach-paneer samosas.

“The girls have been cooking for a week, you know?” the cousin said, glancing at Dia.

In the kitchen, women continued to labor over cutting boards, by the stove, the side buffet, and the sink, and in the backyard, the men hovered over a temporary bar with their drinks and appetizers in hand.

“Phew.” Dia wiped the corner of her mouth with a paper napkin. “Why not have it catered next time?” she said, knowing the hosts had the ease of middle-class American families. “I know someone who does Indian food for cheap.”

The cousin snickered. “In our family, we believe in helping each other.” She nodded at another cousin serving chai to the guests. Dia remembered the line from the first family-in-law party she’d attended. She’d asked one of the women why Samskara ladies hung out exclusively in the kitchen at family socials while men relaxed over drinks and food, never offering help.

The woman shrugged. “It’s always been this way.”

Growing up in Mumbai, Dia had imagined American desis to be more liberal than those in the motherland. She was stunned to see no woman question the gendered division of labor and leisure at Samskara parties, not even those educated in America’s elite schools.

“Must be nice to just sit here and enjoy yourself.” The cousin eyed Dia and slurped her drink.

Dia wagged her finger between Neel and herself. “Are you telling this to us or to me?”

Neel cleared his throat. “You guys enjoyed the islands?” He asked the cousin about her family’s recent trip to the Indian Ocean region.

They had to cancel two of their flights because Mauritius and Reunion were hit by a cyclone, the cousin said. So they stayed in Seychelles throughout their vacation, and boy, when has another week in paradise hurt? “Until, of course, you open your wallet,” the cousin said.

Neel laughed. Dia cheered for the Lakers; they’d scored against the Clippers.

“I should see what the kids are up to,” the cousin said. “Pleasure meeting you.” She bowed in front of Dia. “Madam.”

Dia bowed her head in return, theatrically. “Enjoy.”

“Couldn’t you relax?” Neel turned toward Dia, once the cousin was out of sight.

“She could’ve done the same.”

“But it’s not about her.”

“When will you stop getting defensive about your people?” Dia asked. Your people, that’s how she’d started calling Neel’s endless extended family in Southern California, all within 50 miles of their home in Long Beach.

“I thought we were done with the Hawai’i story?” Neel said.

After three years of dating, Dia moved in with Neel in his house in Long Beach. Instead of developing her own circle of friends in the new city, almost every weekend she’d hung out with Neel at a party planned by his people: a baby shower in Newport, a birthday party in Cerritos, an anniversary party in Marina del Rey, a funeral in Irvine. There was hardly an opportunity to enjoy downtime of her own without landing into a fight with Neel who’d mansplain the importance of family roots to the uprooted immigrant in her. Three years later, Taarini was born, giving her a breather from social responsibilities of a wife and daughter-in-law, but as soon as Dia recovered from childbirth, the cycle started all over again. Between feeding and burping the baby, changing diapers and clothes, folding laundry, washing and sanitizing bottles, and alternating night shifts with Neel, the occasional free time she had during her maternity leave was taken up by her in-laws visiting or hosting a get-together for someone or another’s special occasion, Neel, desperate for fun outside the house, Dia desperate for the same by wanting to stay in and slow down, read, watch TV, or do nothing by the beach. Even when they decided to take a vacation to Hawai’i after Taarini’s first birthday, a parental milestone, Neel had gone ahead and invited two cousins and their families from the Bay Area—the conversation casually came up over the phone, he told Dia afterward, who was livid about not being asked. It’s not like she didn’t enjoy hanging out with his people; she got along well with most. What frustrated her was Neel’s need for good times that constantly needed Dia’s presence among his people while her own family lived oceans away in India, so Neel never had to choose between his leisure and spousely duties the way she constantly had to. Worse, as a man in the role of a son or a son-in-law, he would never be judged by his family or hers in ways that a desi daughter-in-law inevitably is when she chooses to honor her needs over those of her adopted family—a gender dynamic invisible to Neel and hypervisible to Dia.

She wiped the samosa crumbs on her fingers with a napkin and pulled her hair back into a ponytail. “We are done,” she said. “But if you can’t hear sexist sarcasms from your people, don’t blame me for noticing.”

“Yo, babe. Can we have a drama-free evening?” Neel drank the last of his old-fashioned. “For once?”

“Cool, dude.” Dia took a big sip of Kingfisher. Another one of their classic drills: If husband is upset over something, he deserves empathy. If wife does the same, ain’t she a drama queen? “Me play your social Barbie,” she said.

Neel stared at the Gaia Yoga commercial on TV and the ubiquitous bliss on gora faces. “I’m getting another drink.” He got up and left.

“Happy hour, folks.” Dia raised her beer bottle toward the elders in the living room. Beta, try not to think so much, ekdum cool you stay, she heard an auntie in her head.

For the rest of the evening, Neel hung out by the bar in the backyard with his cousin brothers including Kiran, who arrived without his wife, Gul, as she was travelling for work. Dia went to the backyard to say hello to Kiran. She wanted to chat longer with him but decided to stay out of Neel’s sight. Benefit of doubt, always give the other the benefit of doubt, another auntie spoke in her head as she entered the kitchen. She placed nonalcoholic drinks on a large tray and served them to the elders in the living room: mango lassi, coconut water, watermelon and pomegranate juice. Maybe Neel’s cousin sister didn’t mean to be sarcastic. As she helped herself to the last coconut water resting on her tray, she spotted Maya and Sherry in the farthest corner of the living room sipping a Kingfisher. She rushed toward them and they exchanged a giddy, girlie hug.

“You surviving my cousin?” Maya asked.

“Him more than the family,” Dia said. “No offense.”

“Yes offense.”

“Not all family, silly.” Dia picked a food crumb out of Maya’s hair.

“Name the victim,” Sherry said.

Dia told them about their argument over Hawai’i. “Our first holiday in two fucking years! If he could have it his way, we’d have shared the honeymoon suite with his family.” Dia dug a fork into the coconut meat.

“So, wait.” Sherry cupped a palm under her cheek. “It’s bad if we watch you two make a baby?”

Dia and Maya laughed.

“Welcome to the family.” Maya aimed her Kingfisher toward the uncles and aunties. “It’s in our blood. The Samskaras do everything in herds.” She pointed to the kids running around them. “All these were likely made together too.”

Dia and Sherry laughed.

“And the irony of it?” Maya took a sip of her beer. “I move to the East Coast, marry WASP men twice, but look at me now—back to my herd, sipping my Kingfisher.”

“I don’t mind the herd—” Dia tapped her fork against the coconut’s hollow head. “As long as he remembers I’ve married him, not his whole family.”

“Girlfriend. What desi chick married her husband alone?”

Dia rolled her eyes.

“Give it time. He’ll eventually cut the umbilical cord,” Sherry said, flashing her teeth so the women could check her smile for lipstick residue.

Dia pointed her finger toward an upper canine.

Sherry ran her tongue over it. “He’s never stepped outside the herd,” she said.

“Until then, deal with the roller coaster?”

“You signed up for the amusement park, babe,” Sherry said. She was casually dating since she broke up with her last boyfriend three years ago.

“So buck up—” Dia scraped more of the young coconut’s meat. “And suck up?” She looked at the girls.

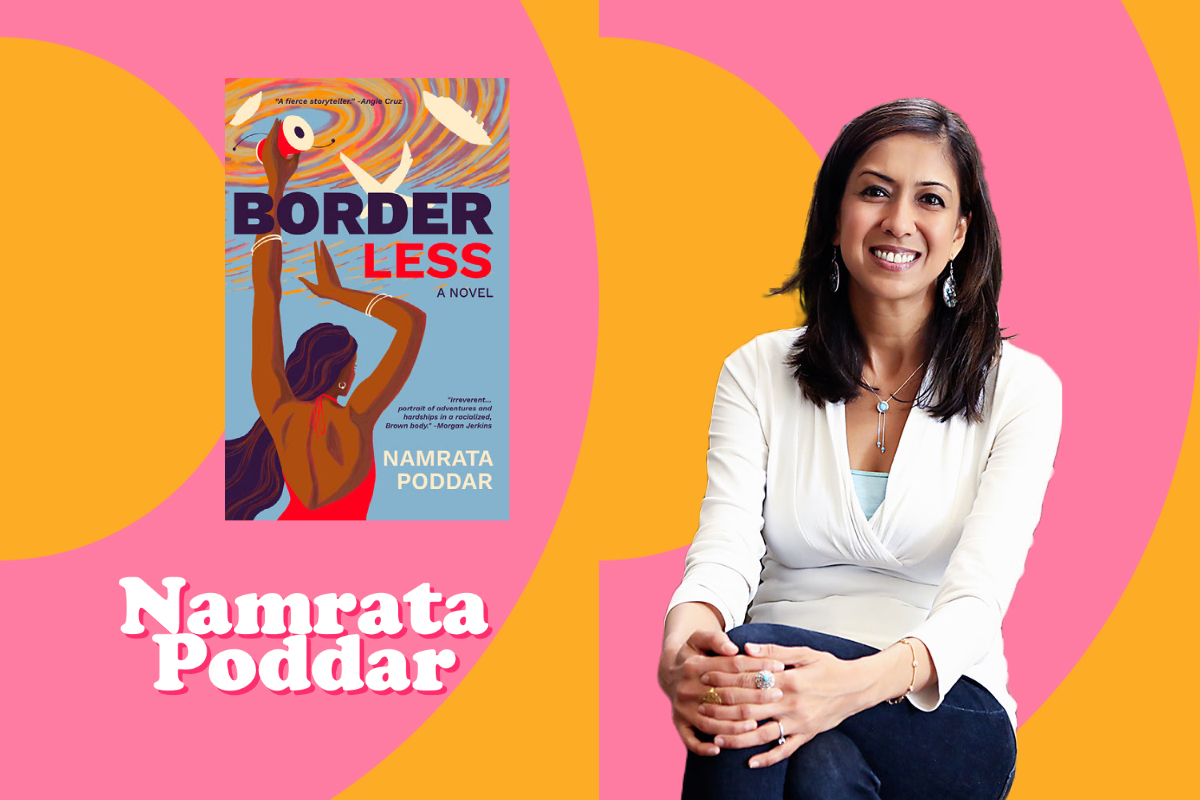

Adapted from Border Less: A Novel by Namrata Poddar (7.13 Books and HarperCollins India, 2022).